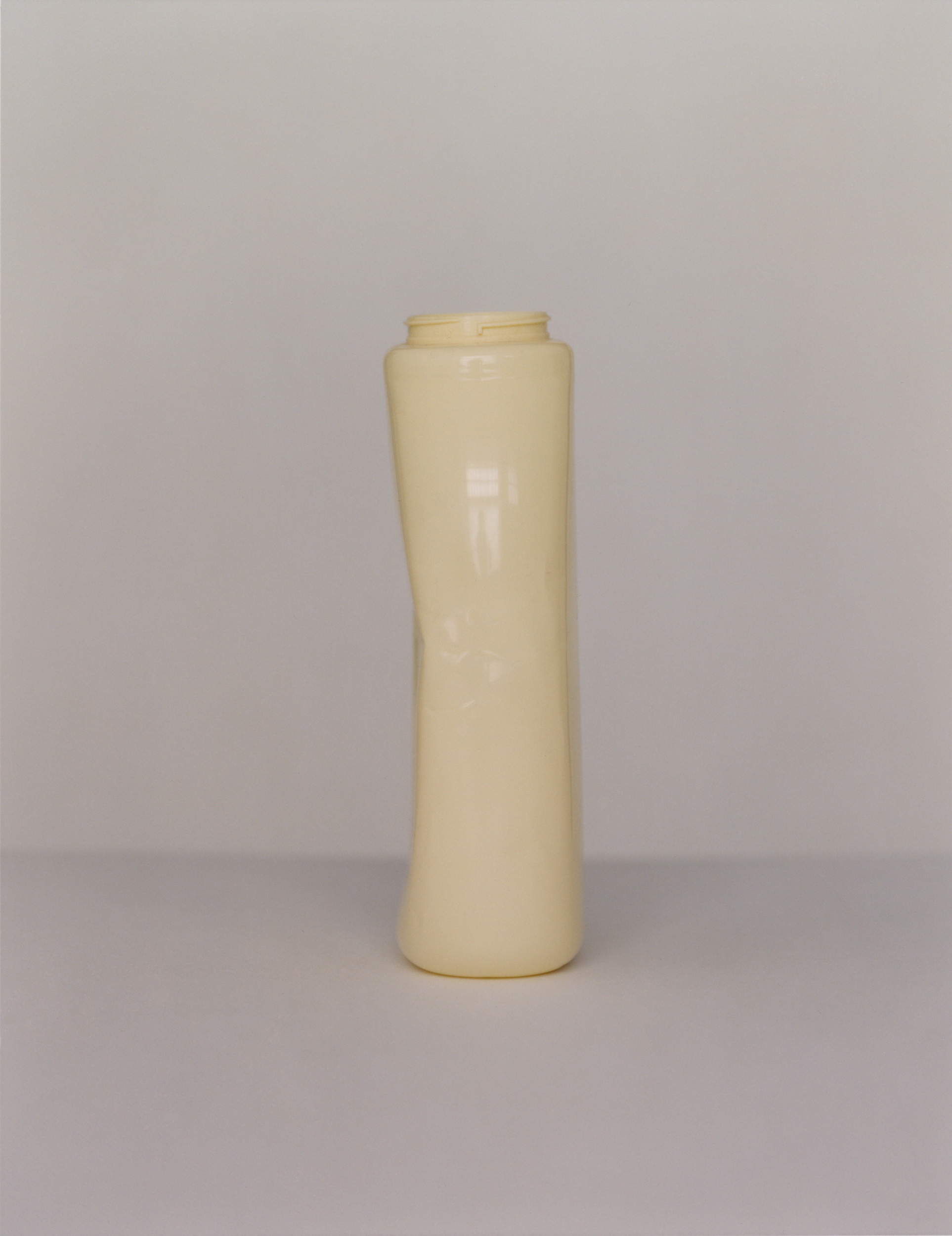

In this way a laboratory comes into being, a sanitized sphere in which nothing but the essential visibility of the objects has a place. Goedicke’s photographs call up memories of advertising pictures created under studio conditions: pictures with reflective surfaces, meticulous lighting, and immaculately groomed objects, frequently in lurid colors. He is alluding to this idiom while at the same time subverting it. As a form of camouflage he utilizes elements of its grammar, but he does so in order to formulate a contradictory statement. For where the language of advertising wishes to communicate the semblance of unambiguous clarity, (...) it is precisely the multiple layers of the objects, the inexhaustible dephts of their appearance that Goedicke’s pictures plumb. (...)

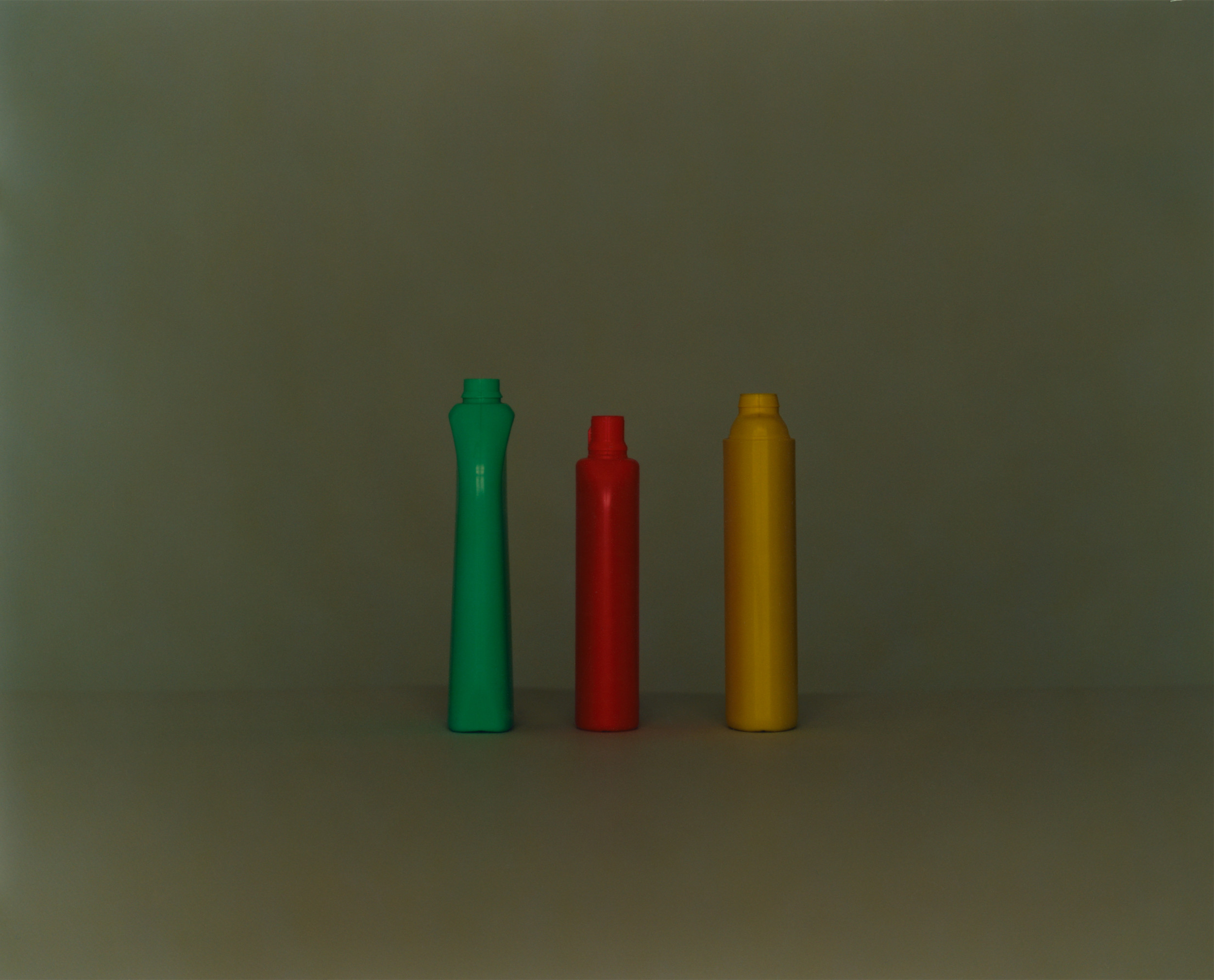

But what interests Goedicke more than anything else is how the putative identity of the single object is altered when it enters into a dialogue with others, and what happens when, say, the background changes? These seems to be formal questions but behind them the fundamentally questionable nature of reality looms. By that he means the process of constant change where the visible is in a permanent state of flux for which we have no concepts, know no reasons, but for which, nevertheless, modern art by trying many and varied approaches has developed a pictioral language. (...)

His pictures are an affirmation not of single objects with an unquestionable identity which sets them apart from one another, but rather of a constant transfer among them. Their contours are only a distinct line at their outer edge. But when they stand alongside one an-other it is the spaces between them that are thematized, a zone of color exchange full of implications which transcends the physical boundaries. (...)

More important than the objects here is what is made visible between them. From these pictures in particular it is clear that the visible can reach beyond the nameable.

From: Heinz Liesbrock, Zwischen dem Sichtbaren – Claus Goedickes Stilleben,

issued in Goedicke Hatje Cantz Verlag 2001