Walker Evans said about unconscious arrangements of objects in a domestic environment, which he photographed in the 1930s, that they are “a piece of the anatomy of somebody’s living.” Around 1910, Eugène Atget observed something similar in the apartments of the Intérieurs Parisiens, and Thomas Ruff in the early 1990s in his Interieurs.

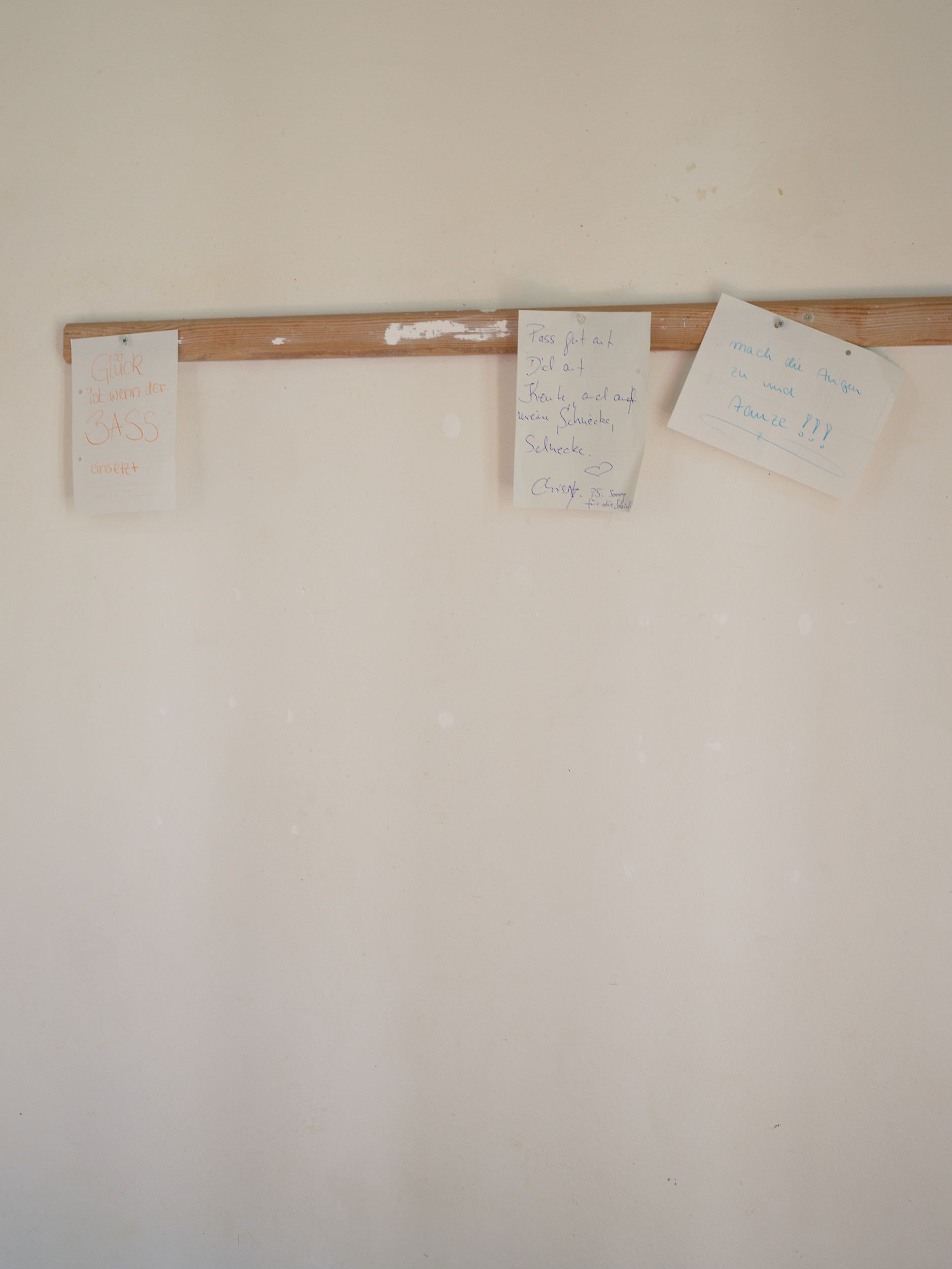

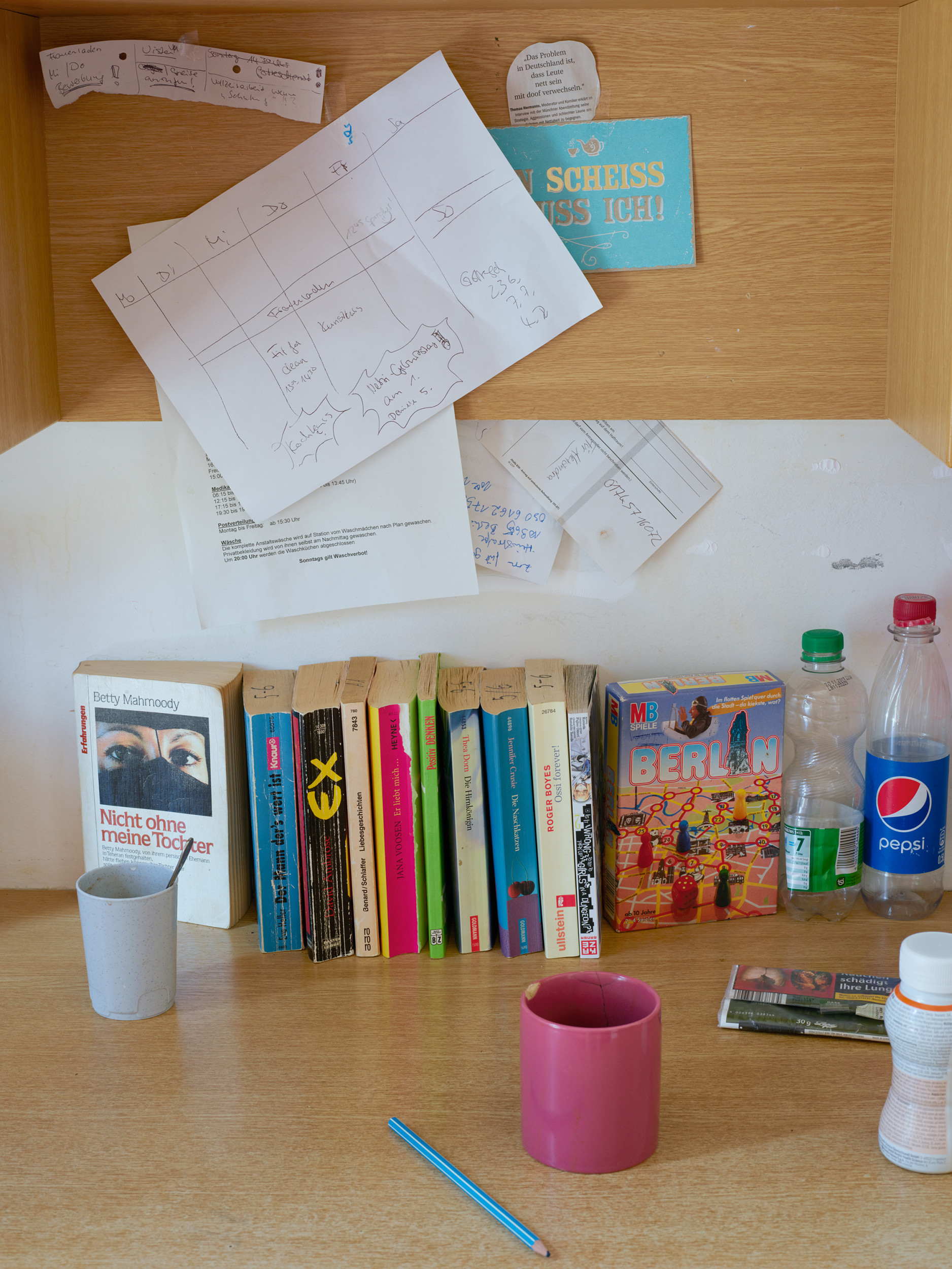

My exploration of the world of things continues with the photographs of prison cells. What does the anatomy of life Evans speaks of look like there?

What remains of the possibilities of interacting with the world in its material manifestations? What personal possessions remain? Is the loss of freedom, and the limitation of personal development articulated in how one’s personal environment is decorated, in a situation where due to the conditions of imprisonment hardly anything private remains?

Based on the assumption that humans inscribe themselves into the world, and fashion it, through the invention and use of objects, and thus claim their place in the world, I look at things in prison cells. The cell photographs pose the question of how much room for maneuver, and how much possibility for personal development, is granted to people in prison.

A second aspect of the series Zellen can best be described with a quotation by the South African politician Nelson Mandela (1918-2013): “No one truly knows a nation unto one has been inside its jails.” This truth remains valid, even though there is a significant difference between the figure of Nelson Mandela and the significance of his imprisonment on Robben Island from 1963 to 1990 on the one hand, and the conditions of detention in today’s German prisons on the other.

For every society, it is an important, always present question how it punishes crime, how such punishments are carried out, and what the public knows about it. The large majority of people has no idea what the inside of a prison looks like. Hardly anyone except the inmates and their families, and the staff working there, has ever seen the inside of a prison. A prison constitutes a parallel society, informed by clichés to be found in the media, literature, and film.

In these photographs of prison cells, two societal aspects become clearer: the abstract, superordinate idea of imprisonment as a regulatory measure as well as the concrete image that the imprisoned individual can create of himself or herself under the conditions of imprisonment.